Which Of The Following Animals Has Fur That Changes Color With The Season?

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of brute fur. Since the establishment of a world fur marketplace in the early modern period, furs of boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals have been the most valued. Historically the trade stimulated the exploration and colonization of Siberia, northern North America, and the South Shetland and Southward Sandwich Islands.

Today the importance of the fur trade has macerated; it is based on pelts produced at fur farms and regulated fur-bearer trapping, but has get controversial. Animal rights organizations oppose the fur merchandise, citing that animals are brutally killed and sometimes skinned alive.[ane] Fur has been replaced in some habiliment past synthetic imitations, for example, as in ruffs on hoods of parkas.

Russian fur trade

Before the European colonization of the Americas, Russia was a major supplier of fur pelts to Western Europe and parts of Asia. Its trade developed in the Early Middle Ages ( 500–1000 AD/CE ), first through exchanges at posts around the Baltic and Black seas. The primary trading market destination was the German city of Leipzig.[2] Kievan Rus', the starting time Russian State, was the first supplier of the Russian Fur Merchandise.[3]

Originally, Russia exported raw furs, consisting in most cases of the pelts of martens, beavers, wolves, foxes, squirrels and hares. Between the 16th and 18th centuries, Russians began to settle in Siberia, a region rich in many mammal fur species, such as Arctic fox, lynx, sable, ocean otter and stoat (ermine). In a search for the prized sea otter pelts, first used in Cathay, and later for the northern fur seal, the Russian Empire expanded into Northward America, notably Alaska. From the 17th through the second half of the 19th century, Russia was the world'southward largest supplier of fur. The fur merchandise played a vital role in the development of Siberia, the Russian Far East and the Russian colonization of the Americas. As recognition of the importance of the merchandise to the Siberian economy, the sable is a regional symbol of the Ural Sverdlovsk Oblast and the Siberian Novosibirsk, Tyumen and Irkutsk Oblasts of Russia.[4]

Fur muff manufacturer's 1949 advertisement

European contact with Northward America, with its vast forests and wildlife, peculiarly the beaver, led to the continent becoming a major supplier in the 17th century of fur pelts for the fur felt hat and fur trimming and garment trades of Europe. Fur was relied on to make warm clothing, a critical consideration prior to the organization of coal distribution for heating. Portugal and Spain played major roles in fur trading after the 15th century with their concern in fur hats.[5]

Siberian fur trade

From as early every bit the tenth century, merchants and boyars of Novgorod had exploited the fur resources "beyond the portage", a watershed at the White Lake that represents the door to the entire northwestern part of Eurasia. They began by establishing trading posts along the Volga and Vychegda river networks and requiring the Komi people to give them furs as tribute. Novgorod, the chief fur-trade center prospered as the easternmost trading mail of the Hanseatic League. Novgorodians expanded farther east and north, coming into contact with the Pechora people of the Pechora River valley and the Yugra people residing virtually the Urals. Both of these native tribes offered more resistance than the Komi, killing many Russian tribute-collectors throughout the 10th and eleventh centuries.[six] As Muscovy gained more power in the 15th century and proceeded in the "gathering of the Russian lands", the Muscovite land began to rival the Novgorodians in the North. During the 15th century Moscow began subjugating many native tribes. One strategy involved exploiting antagonisms betwixt tribes, notably the Komi and Yugra, by recruiting men of one tribe to fight in an regular army against the other tribe. Campaigns confronting native tribes in Siberia remained insignificant until they began on a much larger scale in 1483 and 1499.[seven]

Also the Novgorodians and the indigenes, Muscovites also had to contend with the various Muslim Tatar khanates to the due east of Muscovy. In 1552 Ivan 4, the Tsar of All the Russias, took a significant footstep towards securing Russian hegemony in Siberia when he sent a large regular army to assail the Kazan Tartars and ended up obtaining the territory from the Volga to the Ural Mountains. At this bespeak the phrase "ruler of Obdor, Konda, and all Siberian lands" became part of the championship of the Tsar in Moscow.[8] Even and so, problems ensued afterwards 1558 when Ivan IV sent Grigory Stroganov (ca 1533–1577) to colonize land on the Kama and to subjugate and enserf the Komi living in that location. The Stroganov family before long came into conflict (1573) with the Khan of Sibir whose land they encroached on. Ivan told the Stroganovs to hire Cossack mercenaries to protect the new settlement from the Tatars. From ca 1581 the ring of Cossacks led past Yermak Timofeyevich fought many battles that eventually culminated in a Tartar victory (1584) and the temporary finish to Russian occupation in the expanse. In 1584 Ivan'south son Fyodor sent military governors (voivodas) and soldiers to repossess Yermak conquests and officially to addendum the state held past the Khanate of Sibir. Similar skirmishes with Tartars took place across Siberia equally Russian expansion continued.[9]

Russian conquerors treated the natives of Siberia every bit hands exploited enemies who were inferior to them. As they penetrated deeper into Siberia, traders built outposts or winter lodges called zimovya where they lived and collected fur tribute from native tribes. By 1620 Russia dominated the land from the Urals eastward to the Yenisey valley and to the Altai Mountains in the south, comprising about 1.25 million foursquare miles of land.[10] Furs would become Russian federation's largest source of wealth during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Keeping up with the advances of Western Europe required significant capital letter and Russia did not have sources of gilt and silver, but it did have furs, which became known as "soft gold" and provided Russian federation with hard currency. The Russian regime received income from the fur trade through two taxes, the yasak (or iasak) tax on natives and the 10% "Sovereign Tithing Revenue enhancement" imposed on both the take hold of and sale of fur pelts.[11] Fur was in great demand in Western Europe, particularly sable and marten, since European forest resource had been over-hunted and furs had become extremely scarce. Fur trading allowed Russia to purchase from Europe goods that information technology lacked, similar lead, tin, precious metals, textiles, firearms, and sulphur. Russian federation too traded furs with Ottoman Turkey and other countries in the Eye East in substitution for silk, textiles, spices, and dried fruit. The high prices that sable, black play a joke on, and marten furs could generate in international markets spurred a "fur fever" in which many Russians moved to Siberia as independent trappers. From 1585 to 1680, tens of thousands of sable and other valuable pelts were obtained in Siberia each yr.[12]

The primary way for the Muscovite land to obtain furs was by exacting a fur tribute from the Siberian natives, called a yasak. Yasak was usually a fixed number of sable pelts which every male tribe fellow member who was at least fifteen years old had to supply to Russian officials. Officials enforced yasak through compulsion and past taking hostages, commonly the tribe chiefs or members of the main'south family. At offset, Russians were content to trade with the natives, exchanging appurtenances similar pots, axes, and beads for the prized sables that the natives did non value, but greater demand for furs led to violence and force becoming the principal means of obtaining the furs. The largest problem with the yasak system was that Russian governors were prone to corruption because they received no salary. They resorted to illegal means of getting furs for themselves, including bribing customs officials to let them to personally collect yasak, extorting natives past exacting yasak multiple times over, or requiring tribute from independent trappers.[13]

Russian fur trappers, called promyshlenniki, hunted in one of two types of bands of 10–fifteen men, called vatagi . The first was an independent band of blood relatives or unrelated people who contributed an equal share of the hunting-expedition expenses; the second was a band of hired hunters who participated in expeditions fully funded by the trading companies which employed them. Members of an independent vataga cooperated and shared all necessary work associated with fur trapping, including making and setting traps, building forts and camps, stockpiling firewood and grain, and fishing. All fur pelts went into a common pool that the band divided equally among themselves after Russian officials exacted the tithing tax. On the other hand, a trading company provided hired fur-trappers with the money needed for transportation, food, and supplies, and once the hunt was finished, the employer received ii-thirds of the pelts and the remaining ones were sold and the gain divided evenly amidst the hired laborers. During the summer, promyshlenniki would set up a summertime campsite to stockpile grain and fish, and many engaged in agricultural piece of work for extra coin. During late summertime or early on fall the vatagi left their hunting grounds, surveyed the area, and set up a winter camp. Each fellow member of the grouping fix at least ten traps and the vatagi divided into smaller groups of 2 to iii men who cooperated to maintain certain traps. Promyshlenniki checked traps daily, resetting them or replacing bait whenever necessary. The promyshlenniki employed both passive and active hunting-strategies. The passive approach involved setting traps, while the agile approach involved the employ of hunting-dogs and of bows-and-arrows. Occasionally, hunters also followed sable tracks to their burrows, around which they placed nets, and waited for the sable to emerge.[fourteen]

The hunting flavour began around the time of the showtime snow in October or November and connected until early on spring. Hunting expeditions lasted two to 3 years on average simply occasionally longer. Because of the long hunting season and the fact that passage back to Russian federation was hard and costly, beginning around the 1650s–1660s many promyshlenniki chose to stay and settle in Siberia.[fifteen] From 1620 to 1680 a total of 15,983 trappers operated in Siberia.[16]

Due north American fur merchandise

The North American fur trade began as early on every bit the 1500s betwixt Europeans and First Nations (encounter: Early on French Fur Trading) and was a central part of the early history of contact between Europeans and the native peoples of what is now the United States and Canada. In 1578 there were 350 European fishing vessels at Newfoundland. Sailors began to trade metallic implements (particularly knives) for the natives' well-worn pelts. The first pelts in demand were beaver and sea otter, as well every bit occasionally deer, bear, ermine and skunk.[17]

Fur robes were blankets of sewn-together, native-tanned, beaver pelts. The pelts were called brush gras in French and "glaze beaver" in English, and were shortly recognized by the newly developed felt-lid making manufacture every bit particularly useful for felting. Some historians, seeking to explain the term brush gras, accept assumed that glaze beaver was rich in human oils from having been worn and so long (much of the pinnacle-hair was worn away through usage, exposing the valuable under-wool), and that this is what made it attractive to the hatters. This seems unlikely, since grease interferes with the felting of wool, rather than enhancing information technology.[eighteen] By the 1580s, beaver "wool" was the major starting material of the French felt-hatters. Hat makers began to use it in England before long after, particularly later Huguenot refugees brought their skills and tastes with them from France.

Early arrangement

General map of the "Beaver Hunting Grounds" described in "Deed from the Five Nations to the King, of their Beaver Hunting Ground," also known as the Nanfan Treaty of 1701

Captain Chauvin made the first organized attempt to control the fur trade in New French republic. In 1599 he acquired a monopoly from Henry IV and tried to found a colony most the rima oris of the Saguenay River at Tadoussac. French explorers, like Samuel de Champlain, voyageurs, and Coureur des bois, such as Étienne Brûlé, Radisson, La Salle, and Le Sueur, while seeking routes through the continent, established relationships with Amerindians and continued to expand the merchandise of fur pelts for items considered 'common' by the Europeans. Mammal winter pelts were prized for warmth, peculiarly beast pelts for beaver wool felt hats, which were an expensive status symbol in Europe. The demand for beaver wool felt hats was such that the beaver in Europe and European Russia had largely disappeared through exploitation.

In 1613 Dallas Carite and Adriaen Block headed expeditions to establish fur trade relationships with the Mohawk and Mohican. By 1614 the Dutch were sending vessels to secure large economic returns from fur trading. The fur merchandise of New Netherland, through the port of New Amsterdam, depended largely on the trading depot at Fort Orange (now Albany) on the upper Hudson River. Much of the fur is believed to have originated in Canada, smuggled due south past entrepreneurs who wished to avoid the colony's government-imposed monopoly there.

England was slower to enter the American fur trade than France and the Dutch Commonwealth, but as soon as English colonies were established, development companies learned that furs provided the best way for the colonists to remit value dorsum to the female parent state. Furs were being dispatched from Virginia soon after 1610, and the Plymouth Colony was sending substantial amounts of beaver to its London agents through the 1620s and 1630s. London merchants tried to take over France's fur trade in the St Lawrence River valley. Taking reward of 1 of England's wars with France, Sir David Kirke captured Quebec in 1629 and brought the yr's produce of furs dorsum to London. Other English merchants also traded for furs around the Saint Lawrence River region in the 1630s, but these were officially discouraged. Such efforts ceased equally France strengthened its presence in Canada.

Much of the fur trade in Northward America during the 17th and 18th centuries was dominated by the Canadian fur aircraft network that developed in New French republic under the fur monopoly held first by the Company of Ane Hundred Associates, then followed in 1664 past the French West Republic of india Company,[19] steadily expanding fur trapping and shipping across a network of frontier forts farther west that eventually went all the mode to modern day Winnipeg in Western Canada by the mid 1700s,[20] coming into direct contact and opposition with the English fur trappers stationed out of York Mill at Hudson Bay. Meanwhile, the New England fur merchandise expanded as well, not only inland, but n along the coast into the Bay of Fundy region. London's access to high-quality furs was profoundly increased with the takeover of New Amsterdam, whereupon the fur trade of that colony (now called New York) roughshod into English easily with the 1667 Treaty of Breda.

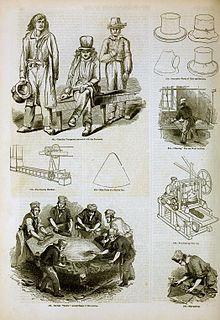

Fur traders in Canada, trading with Native Americans, 1777

In 1668 the English fur trade entered a new stage. Two French citizens, Pierre-Esprit Radisson and Médard des Groseilliers, had traded with smashing success west of Lake Superior in 1659–sixty, but upon their render to Canada, most of their furs were seized by the authorities. Their trading voyage had convinced them that the best fur country was far to the north and westward, and could best be reached by ships sailing into Hudson Bay. Their treatment in Canada suggested that they would not find support from French republic for their scheme. The pair went to New England, where they institute local financial support for at least two attempts to reach Hudson Bay, both unsuccessful. Their ideas had reached the ears of English regime, even so, and in 1665 Radisson and Groseilliers were persuaded to get to London. After some setbacks, a number of English investors were found to back another effort for Hudson Bay.

Two ships were sent out in 1668. One, with Radisson aboard, had to plow dorsum, but the other, the Nonsuch, with Groseilliers, did penetrate the bay. At that place she was able to trade with the indigenes, collecting a fine cargo of beaver skins before the expedition returned to London in October 1669. The delighted investors sought a royal charter, which they obtained the next yr. This lease established the Hudson'south Bay Company and granted it a monopoly to trade into all the rivers that emptied into Hudson Bay. From 1670 onwards, the Hudson'due south Bay Company sent two or three trading ships into the bay every twelvemonth. They brought back furs (mainly beaver) and sold them, sometimes past individual treaty but commonly past public sale. The beaver was bought mainly for the English hat-making trade, while the fine furs went to the Netherlands and Germany.

Meanwhile, in the Southern colonies, a deerskin trade was established around 1670, based at the export hub of Charleston, South Carolina. Word spread among Native hunters that the Europeans would exchange pelts for the European-manufactured appurtenances that were highly desired in native communities. Carolinan traders stocked axe heads, knives, awls, fish hooks, cloth of various type and color, woolen blankets, linen shirts, kettles, jewelry, glass beads, muskets, ammunition and powder to exchange on a 'per pelt' basis.

Colonial trading posts in the southern colonies as well introduced many types of alcohol (specially brandy and rum) for trade.[21] European traders flocked to the Northward American continent and made huge profits from the exchange. A metallic axe head, for example, was exchanged for one beaver pelt (likewise chosen a 'beaver coating'). The aforementioned pelt could fetch enough to purchase dozens of axe heads in England, making the fur merchandise extremely assisting for the Europeans. The Natives used the iron axe heads to supervene upon rock axe heads which they had made by hand in a labor-intensive procedure, so they derived substantial benefits from the trade as well. The colonists began to encounter the sick effects of alcohol on Natives, and the chiefs objected to its sale and trade. The Imperial Proclamation of 1763 prohibited auction by European settlers of alcohol to the Indians in Canada, following the British takeover of the territory subsequently information technology defeated France in the 7 Years' State of war (known as the French and Indian War in Northward America).

Following the British take over of Canada from France, the control of the fur trade in Northward America became consolidated under the British authorities for a time, until the United States was created and became a major source for furs being shipped to Europe equally well in the Nineteenth Century,[22] forth with the largely unsettled territory of Russian America, which became a significant source of furs besides during that menses.[23] The fur trade began to significantly turn down starting in the 1830s, following changing attitudes and fashions in Europe and America which no longer centered around sure articles of clothing equally much such as beaver skin hats, which had fueled the growing demand for furs, driving the creation and expansion of the fur trade in the 17th and 18th centuries, although new trends every bit well as occasional revivals of prior fashions would cause the fur trade to ebb and menstruum right up to the present.[24]

Socioeconomic ties

Often, the political benefits of the fur merchandise became more important than the economic aspects. Trade was a way to forge alliances and maintain expert relations between different cultures. The fur traders were men with capital and social standing. Frequently younger men were single when they went to North America to enter the fur trade; they fabricated marriages or cohabited with loftier-ranking Indian women of similar condition in their own cultures. Fur trappers and other workers commonly had relationships with lower-ranking women. Many of their mixed-race descendants adult their own civilization, now called Métis in Canada, based and then on fur trapping and other activities on the frontier.

In some cases both Native American and European-American cultures excluded the mixed-race descendants. If the Native Americans were a tribe with a patrilineal kinship system, they considered children born to a white father to be white, in a type of hypodescent classification, although the Native female parent and tribe might intendance for them. The Europeans tended to classify children of Native women every bit Native, regardless of the father, similar to the hypodescent of their nomenclature of the children of slaves. The Métis in the Canadian Red River region were so numerous that they adult a creole language and culture. Since the late 20th century, the Métis have been recognized in Canada equally a Offset Nations ethnic grouping. The interracial relationships resulted in a two-tier mixed-race grade, in which descendants of fur traders and chiefs accomplished prominence in some Canadian social, political, and economic circles. Lower-class descendants formed the bulk of the separate Métis culture based on hunting, trapping and farming.

Because of the wealth at stake, different European-American governments competed with various native societies for command of the fur trade. Native Americans sometimes based decisions of which side to support in times of war in relation to which people had provided them with the best trade goods in an honest manner. Because trade was so politically important, the Europeans tried to regulate information technology in hopes (often futile) of preventing abuse. Unscrupulous traders sometimes cheated natives by plying them with alcohol during the transaction, which subsequently angry resentment and oftentimes resulted in violence.

In 1834 John Jacob Astor, who had created the huge monopoly of the American Fur Visitor, withdrew from the fur trade. He could run across the decline in fur animals and realized the market was irresolute, as beaver hats went out of style. Expanding European settlement displaced native communities from the best hunting grounds. European need for furs subsided equally fashion trends shifted. The Native Americans' lifestyles were altered by the merchandise. To continue obtaining European appurtenances on which they had become dependent and to pay off their debts, they ofttimes resorted to selling land to the European settlers. Their resentment of the forced sales contributed to time to come wars.

Later the U.s. became contained, it regulated trading with Native Americans by the Indian Intercourse Act, first passed on July 22, 1790. The Bureau of Indian Affairs issued licenses to trade in the Indian Territory. In 1834 this was divers every bit most of the Usa west of the Mississippi River, where mount men and traders from Mexico freely operated.

Early exploration parties were often fur-trading expeditions, many of which marked the first recorded instances of Europeans' reaching particular regions of North America. For case, Abraham Forest sent fur-trading parties on exploring expeditions into the southern Appalachian Mountains, discovering the New River in the process. Simon Fraser was a fur trader who explored much of the Fraser River in British Columbia.

Part in economical anthropology

Economic historians and anthropologists have studied the fur trade's important role in early Northward American economies, simply they have been unable to concur on a theoretical framework to describe native economic patterns.

John C. Phillips and J.Due west. Smurr tied the fur merchandise to an purple struggle for power, positing that the fur trade served both as an incentive for expanding and equally a method for maintaining dominance. Dismissing the experience of individuals, the authors searched for connections on a global phase that revealed its "loftier political and economical importance."[25] E.E. Rich brought the economical purview downwards a level, focusing on the office of trading companies and their men every bit the ones who "opened up" much of Canada's territories, instead of on the role of the nation-state in opening up the continent.[26]

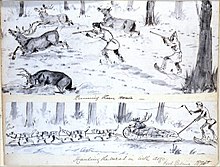

Two Sleighs on a Country Road, Canada, c. 1835–1848. Image includes a multifariousness of fur throws and clothing, including hides of animals non native to Canada.

Rich's other work gets to the heart of the formalist/substantivist debate that dominated the field or, as some came to believe, muddied it. Historians such as Harold Innis had long taken the formalist position, especially in Canadian history, believing that neoclassical economic principles impact not-Western societies simply as they practise Western ones.[27] Starting in the 1950s, yet, substantivists such as Karl Polanyi challenged these ideas, arguing instead that primitive societies could engage in alternatives to traditional Western market place trade; namely, gift trade and administered trade. Rich picked upwards these arguments in an influential article in which he contended that Indians had "a persistent reluctance to have European notions or the bones values of the European approach" and that "English economic rules did non use to the Indian merchandise."[28] Indians were savvy traders, but they had a fundamentally different formulation of property, which confounded their European trade partners. Abraham Rotstein subsequently fit these arguments explicitly into Polanyi'due south theoretical framework, challenge that "administered merchandise was in operation at the Bay and market trade in London."[29]

Trapper's motel in Alaska, 1980s

Arthur J. Ray permanently changed the management of economic studies of the fur merchandise with two influential works that presented a modified formalist position in between the extremes of Innis and Rotstein. "This trading organization," Ray explained, "is incommunicable to characterization neatly as 'gift merchandise', or 'administered trade', or 'marketplace trade', since information technology embodies elements of all these forms."[30] Indians engaged in trade for a diversity of reasons. Reducing them to simple economic or cultural dichotomies, as the formalists and substantivists had done, was a fruitless simplification that obscured more than information technology revealed. Moreover, Ray used trade accounts and account books in the Hudson's Bay Company'due south archives for masterful qualitative analyses and pushed the boundaries of the field'due south methodology. Following Ray's position, Bruce M. White also helped to create a more nuanced film of the complex means in which native populations fit new economic relationships into existing cultural patterns.[31]

Richard White, while albeit that the formalist/substantivist debate was "old, and now tired," attempted to reinvigorate the substantivist position.[32] Echoing Ray'southward moderate position that cautioned confronting easy simplifications, White advanced a simple argument against formalism: "Life was non a business organization, and such simplifications only distort the past."[33] White argued instead that the fur trade occupied part of a "middle ground" in which Europeans and Indians sought to arrange their cultural differences. In the instance of the fur trade, this meant that the French were forced to larn from the political and cultural meanings with which Indians imbued the fur trade. Cooperation, not domination, prevailed.

Nowadays

Co-ordinate to the Fur Constitute of Canada, there are almost 60,000 active trappers in Canada (based on trapping licenses), of whom most 25,000 are indigenous peoples.[34] The fur farming manufacture is present in many parts of Canada.[35] The largest producer of mink and foxes is Nova Scotia which in 2012 generated revenues of well-nigh $150 million and accounted for i quarter of all agricultural production in the Province.[36]

Maritime fur trade

The maritime fur trade was a ship-based fur trade organisation that focused on acquiring furs of sea otters and other animals from the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast and natives of Alaska. The furs were more often than not traded in China for tea, silks, porcelain, and other Chinese goods, which were then sold in Europe and the U.s.. The maritime fur trade was pioneered by the Russians, working e from Kamchatka along the Aleutian Islands to the southern coast of Alaska. British and Americans entered during the 1780s, focusing on what is now the coast of British Columbia. The merchandise boomed effectually the turn of the 19th century. A long flow of reject began in the 1810s. As the body of water otter population was depleted, the maritime fur trade diversified and was transformed, tapping new markets and commodities while continuing to focus on the Northwest Coast and China. It lasted until the middle to tardily 19th century. Russians controlled most of the coast of what is at present Alaska during the entire era. The coast s of Alaska saw trigger-happy contest between, and among, British and American trading vessels. The British were the beginning to operate in the southern sector, only were unable to compete confronting the Americans who dominated from the 1790s to the 1830s. The British Hudson's Bay Visitor entered the coast trade in the 1820s with the intention of driving the Americans away. This was achieved by nearly 1840. In its late flow the maritime fur trade was largely conducted by the British Hudson's Bay Company and the Russian-American Visitor.

The Russian fur traders from Alaska established their largest settlement in California, Fort Ross, in 1812

The term "maritime fur trade" was coined by historians to distinguish the coastal, ship-based fur trade from the continental, land-based fur trade of, for example, the North West Company and the American Fur Company. Historically, the maritime fur merchandise was non known by that name, rather it was usually called the "North Due west Coast trade" or "Due north Due west Merchandise". The term "Northward West" was rarely spelled as the single word "Northwest", as is mutual today.[37]

The maritime fur trade brought the Pacific Northwest coast into a vast, new international trade network, centered on the northward Pacific Ocean, global in telescopic, and based on capitalism but non, for the most part, on colonialism. A triangular trade network emerged linking the Pacific Northwest declension, China, the Hawaiian Islands (only recently discovered by the Western globe), Europe, and the United States (particularly New England). The merchandise had a major effect on the ethnic people of the Pacific Northwest coast, peculiarly the Aleut, Tlingit, Haida, Nuu-chah-nulth, and Chinook peoples. There was a rapid increase of wealth among the Northwest Coast natives, forth with increased warfare, potlatching, slaving, depopulation due to epidemic illness, and enhanced importance of totems and traditional dignity crests.[38] The indigenous culture was not still overwhelmed, it rather flourished, while simultaneously undergoing rapid modify. The use of Chinook Jargon arose during the maritime fur trading era and remains a distinctive aspect of Pacific Northwest culture. Native Hawaiian gild was similarly affected by the sudden influx of Western wealth and technology, besides equally epidemic diseases. The merchandise's effect on China and Europe was minimal. For New England, the maritime fur trade and the significant profits information technology made helped revitalize the region, contributing to the transformation of New England from an agrarian to an industrial society. The wealth generated by the maritime fur trade was invested in industrial development, peculiarly material manufacturing. The New England textile industry in turn had a large outcome on slavery in the United States, increasing the demand for cotton wool and helping make possible the rapid expansion of the cotton fiber plantation arrangement beyond the Deep Due south.[39]

Modern and historical ranges of bounding main otter subspecies

The most profitable furs were those of bounding main otters, especially the northern sea otter, Enhydra lutris kenyoni, which inhabited the coastal waters between the Columbia River to the south and Cook Inlet to the north. The fur of the Californian southern sea otter, E. 50. nereis, was less highly prized and thus less profitable. After the northern body of water otter was hunted to local extinction, maritime fur traders shifted to California until the southern bounding main otter was likewise nearly extinct.[twoscore] The British and American maritime fur traders took their furs to the Chinese port of Guangzhou (County), where they worked within the established County System. Furs from Russian America were mostly sold to Prc via the Mongolian trading town of Kyakhta, which had been opened to Russian trade by the 1727 Treaty of Kyakhta.[41]

Run across likewise

- Beaver Wars

- California Fur Rush

- The Coalition to Abolish the Fur Merchandise

- Coureur des bois

- Fur brigade

- List of fur trading post and forts in Due north America

Footnotes

- ^ "Feature: A Shocking Expect Inside Chinese Fur Farms". PETA.

- ^ Fisher 1943, p. 197.

- ^ Fisher 1943, p. 1.

- ^ Janet Martin, Treasure of the Land of Darkness: The Fur Trade and Its Significance for Medieval Russian federation (2004) p. 204

- ^ Fisher 1943, p. 17.

- ^ Forsyth 1994, p. 2–3.

- ^ Forsyth 1994, p. 28.

- ^ Forsyth 1994, p. 10.

- ^ Forsyth 1994, p. 29-33.

- ^ Forsyth 1994, p. 38.

- ^ Bychkov & Jacobs 1994, p. 73.

- ^ Forsyth 1994, p. 38-40.

- ^ Forsyth 1994, p. 41-42.

- ^ Bychkov & Jacobs 1994, p. 75-80.

- ^ Bychkov & Jacobs 1994, p. lxxx-81.

- ^ Bychkov & Jacobs 1994, p. 74.

- ^ Dolin 2010, p. 16.

- ^ Dolin 2010, p. 46.

- ^ Dolin 2010, p. 105.

- ^ Wallace, Stewart Due west. (1948). The Encyclopedia of Canada. Vol. 2. Toronto: University Assembly of Canada. p. 366.

- ^ "Introduction of alcohol through the fur trade". University of Montana. Archived from the original on 2009-02-26. Retrieved 2019-07-22 .

- ^ United States. Business and Defense Services Administration (January 1966). Fur Facts & Figures: A Survey of the United States Fur Industry. Volume 41. Washington, DC: US Department of Commerce. p. one.

- ^ Miller, Gwen A. (2010). Kodiak Kreol: Communities of Empire in Early Russian America. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press. p. XII.

- ^ Delhomme, PJ (28 November 2021). "Is Trapping in America on the Brink of Extinction, or at the Kickoff of a Comeback?". Outdoor Life . Retrieved 2021-11-29 .

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Phillips, Paul Chrisler; Smurr, J.W. (1961). The Fur Trade. Vol. 2. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Printing. p. 20.

- ^ Rich, Edwin Ernest (1967). The Fur Trade and the Northwest to 1857. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart Limited. p. 296. ISBN9780771074561. OCLC 237371.

- ^ Innis, Harold Adams (1930). Oliver Baty Cunningham Memorial Publication Fund; Ray, Arthur J. (eds.). The Fur Trade in Canada: An Introduction to Canadian Economical History. New Haven: Yale Academy Printing. p. 463. ISBN9780802081964.

- ^ Rich, Eastward.E. (February 1960). "Trade Habits and Economic Motivation Amid the Indians of N America". The Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science. Canadian Economic science Association. 26 (1): 46, 47. doi:10.2307/138817. JSTOR 138817.

- ^ Abraham Rotstein (March 1970). "Karl Polanyi's Concept of Non-Market Trade". The Periodical of Economic History. xxx (1): 123. See also Rotstein (1967). Fur Merchandise and Empire: An Institutional Analysis (PhD diss.). University of Toronto.

- ^ Arthur J. Ray and Donald B. Freeman, Give Us Expert Measure out: An Economic Analysis of Relations between the Indians and the Hudson's Bay Company Before 1763, (Toronto: Academy of Toronto Press, 1978), p. 236.

- ^ White 1984.

- ^ White 1991, p. 94.

- ^ White 1991, p. 95.

- ^ "Canada'due south Fur Merchandise: Facts & Figures". Fur Plant of Canada. Archived from the original on 2012-11-03. Retrieved 2019-07-22 .

- ^ "Fur Statistics, 2010" (PDF). Statistics Canada. Minister of Industry. Government of Canada. October 2011. p. 20. ISSN 1705-4273. Retrieved 2019-07-22 .

- ^ Bundale, Brett (16 January 2013). "Fur farms may not all survive new N.S. rules". The Chronicle Herald. Halifax, Nova Scotia. Archived from the original on 2013-01-18. Retrieved 2013-03-12 .

- ^ Mackie, Richard Somerset (1997). Trading Beyond the Mountains: The British Fur Merchandise on the Pacific 1793–1843. Vancouver: University of British Columbia (UBC) Printing. p. 123. ISBN0-7748-0613-iii.

- ^ For more on the use of crests on the Due north W Coast, see: Reynoldson, Fiona (2000). Native Americans: The Indigenous Peoples of North America. Heinemann. p. 34. ISBN978-0-435-31015-8.

- ^ Farrow, Anne; Joel Lang; Jennifer Frank (2006). Complicity: How the North Promoted, Prolonged, and Profited from Slavery. Random House. pp. fourteen, 25–26, 35–37. ISBN978-0-345-46783-half dozen.

- ^ Fur trade, Northwest Power & Conservation Council

- ^ Haycox, Stephen Due west. (2002). Alaska: An American Colony. University of Washington Press. pp. 53–58. ISBN978-0-295-98249-half-dozen.

Bibliography

General surveys

- Chittenden, Hiram Martin. The American Fur Trade of the Far West: A History of the Pioneer Trading Posts and Early Fur Companies of the Missouri Valley and the Rocky Mountains and the Overland Commerce with Santa Fe. 2 vols. (1902). full text online

- Dolin, Eric Jay (2010). Fur, Fortune, and Empire: The Epic History of the Fur Trade in America (1st ed.). New York: W.Due west. Norton & Company. ISBN978-0-393-06710-1.

- Fisher, Raymond Henry (1943). The Russian Fur Merchandise, 1550-1700. Academy of California Press. p. 275.

- Forsyth, James (viii September 1994). A History of the Peoples of Siberia: Russia's North Asian Colony, 1581–1990. Slavic Review. Vol. 53. Cambridge: Cambridge Academy Press. pp. 905–906. doi:10.2307/2501564. ISBN9780521477710. JSTOR 2501564.

- Voorhis, Ernest, Historic Forts and Trading Posts of the French Authorities and of the English language Fur Trading Companies, 1930 (due east-book -with maps.)

Biographies

- Berry, Don. A Majority of Scoundrels: An Informal History of the Rocky Mountain Fur Company. New York: Harper, 1961.

- Hafen, LeRoy, ed. The Mount Men and the Fur Trade of the Far West. 10 vols. Glendale, California: A.H. Clark Co., 1965–72.

- Lavender, David. Aptitude'due south Fort. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1954.

- Lavander, David. The Fist in the Wilderness. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1964.

- Oglesby, Richard. Manuel Lisa and the Opening of the Missouri Fur Merchandise. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 1963.

- Utley, Robert. A Life Wild and Perilous: Mountain Men and the Paths to the Pacific. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1997.

Economic studies

- Allaire, Bernard. Pelleteries, manchons et chapeaux de brush: les fourrures nord-américaines à Paris 1500–1632, Québec, Éditions du Septentrion, 1999, 295 p. (ISBN 978-2840501619)

- Bychkov, Oleg V.; Jacobs, Mina A. (1994). "Russian Hunters in Eastern Siberia in the Seventeenth Century: Lifestyle and Economy" (PDF). Chill Anthropology. University of Wisconsin Press. 31 (ane): 72–85. JSTOR 40316350.

- Black, Lydia. Russians in Alaska, 1732–1867 (2004)

- Cronon, William. Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England. New York: Loma and Wang, 1983.

- Gibson, James R. Otter Skins, Boston Ships, and China Goods: The Maritime Fur Trade of the Northwest Coast, 1785–1841. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1992.

- Ray, Arthur J. The Canadian fur trade in the industrial historic period (1990)

- Ray, Arthur J., and Donald B. Freeman. "Requite Us Good Measure out": An Economical Assay of Relations between the Indians and the Hudson's Bay Visitor Earlier 1763. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1978.

- Rotstein, Abraham. "Karl Polanyi'southward Concept of Non-Market Trade." The Journal of Economic History 30:i (Mar., 1970): 117–126.

- Vinkovetsky, Ilya. Russian America: an overseas colony of a continental empire, 1804–1867 (2011)

- White, Richard. The Center Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650–1815. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

- White, Richard. The Roots of Dependency: Subsistence, Environment, and Social Alter Among the Choctaws, Pawnees, and Navajos. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1983.

- Brownish, Jennifer S.H. and Elizabeth Vibert, eds. Reading Beyond Words: Contexts for Native History. Peterborough, Ontario; Orchard Park, N.Y.: Broadview Press, 1996.

- Francis, Daniel and Toby Morantz. Partners in Furs: A History of the Fur Trade in Eastern James Bay, 1600–1870. Kingston; Montreal: McGill-Queen'south University Press, 1983.

- Holm, Bill and Thomas Vaughan, eds. Soft Gilt: The Fur Trade & Cultural Exchange on the Northwest Coast of America. Portland, Oregon: Oregon Historical Guild Press, 1990.

- Krech, Shepard III. The Ecological Indian: Myth and History. New York; London: W.W. Norton & Company, 1999.

- Krech, Shepard 3, ed. Indians, Animals, and the Fur Trade: A Critique of Keepers of the Game. Athens: University of Georgia Printing, 1981.

- Martin, Calvin. Keepers of the Game: Indian-Animal Relationships and the Fur Trade. Berkeley; Los Angeles; London: University of California Press, 1978.

- Malloy, Mary. Souvenirs of the Fur Merchandise: Northwest Declension Indian Art and Artifacts Collected by American Mariners, 1788–1844. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Peabody Museum Press, 2000.

- Ray, Arthur J. Indians in the Fur Trade: Their Role as Trappers, Hunters, and Middlemen in the Lands Southwest of Hudson Bay, 1660–1870. Toronto; Buffalo; London: University of Toronto Printing, 1974.

- Vibert, Elizabeth. Trader's Tales: Narratives of Cultural Encounters in the Columbia Plateau, 1807–1846. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Printing, 1997.

- Brown, Jennifer South.H. Strangers in Claret: Fur Trade Company Families in Indian Country. Vancouver; London: University of British Columbia Press, 1980.

- Brown, Jennifer S.H. and Jacqueline Peterson, eds. The New Peoples: Being and Becoming Métis in Northward America. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Printing, 1985.

- Giraud, Marcel. The Métis in the Canadian Westward. Translated by George Woodcock. Edmonton, Canada: University of Alberta Press, 1986.

- Gitlin, Jay. The Conservative Frontier: French Towns, French Traders & American Expansion, Yale Academy Printing, 2010

- Nicks, John. "Orkneymen in the HBC, 1780–1821." In Old Trails and New Directions: Papers of the Third North American Fur Trade Conference. Edited by Carol M. Judd and Arthur J. Ray, 102–26. Toronto: Academy of Toronto Press, 1980.

- Podruchny, Carolyn. Making the Voyageur World: Travelers and Traders in the North American Fur Merchandise. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2006.

- Podruchny, Carolyn. "Werewolves and Windigos: Narratives of Cannibal Monsters in French-Canadian Voyageur Oral Tradition." Ethnohistory 51:4 (2004): 677–700.

- Sleeper-Smith, Susan. Indian Women and French Men: Rethinking Cultural See in the Western Great Lakes. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2001.

- Van Kirk, Sylvia. Many Tender Ties: Women in Fur-Trade Society, 1670–1870. Winnipeg: Watson & Dwywer, 1999.

Regional histories

- Allen, John L. "The Invention of the American West." In A Continent Comprehended, edited by John L. Allen. Vol. 3 of North American Exploration, edited by John 50. Allen, 132–189. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1997.

- Braund, Kathryn E. Kingdom of the netherlands. Deerskins and Duffels: The Creek Indian Trade with Anglo-America, 1685–1815. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2008.

- Faragher, John Mack. "Americans, Mexicans, Métis: A Community Approach to the Comparative Study of North American Frontiers." In Under an Open Sky: Rethinking America's Western Past, edited past William Cronon, George Miles, and Jay Gitlin, 90–109. New York; London: W.W. Norton & Company, 1992.

- Gibson, James R. Otter Skins, Boston Ships, and Communist china Appurtenances: The Maritime Fur Trade of the Northwest Coast, 1785–1841. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1992.

- Gibson, Morgan Arrell. Yankees in Paradise: The Pacific Basin Frontier. Albuquerque: University of New United mexican states Printing, 1993.

- Keith, Lloyd, and John C. Jackson. The Fur Trade Take a chance: North West Company on the Pacific Slope, 1800–1820 (Pullman: Washington State University Press, 2016). xiv, 336 pp.

- Malloy, Mary. "Boston Men" on the Northwest Declension: The American Maritime Fur Trade 1788–1844. Kingston, Ontario; Fairbanks, Alaska: The Limestone Press, 1998.

- Panagopoulos, Janie Lynn. "Traders in Time". River Road Publications, 1993.

- Ronda, James P. Astoria & Empire. Lincoln, Nebraska; London: University of Nebraska Printing, 1990.

- Weber, David. The Taos Trappers: The Fur Trade in the Far Southwest, 1540–1846. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 1971.

- White, Richard (27 September 1991). Hoxie, Frederick E.; William 50. Clements Library; Salisbury, Neal (eds.). The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Corking Lakes Region, 1650–1815. Journal of Anthropological Research. Vol. 49. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 283–286. doi:x.1017/CBO9780511976957. ISBN9780521371049. JSTOR 3630498.

- Wishart, David J. The Fur Trade of the American Westward, 1807–1840: A Geographical Synthesis. Lincoln, Nebraska; London: University of Nebraska Press, 1979.

Papers of the North American Fur Trade Conferences

The papers from the Due north American Fur Trade conferences, which are held approximately every 5 years, not only provide a wealth of articles on disparate aspects of the fur merchandise, but also can be taken together every bit a historiographical overview since 1965. They are listed chronologically below. The third briefing, held in 1978, is of item annotation; the ninth conference, which was held in St. Louis in 2006, has not yet published its papers.

- Morgan, Dale Lowell, ed. Aspects of the Fur Trade: Selected Papers of the 1965 Northward American Fur Trade Conference. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Club, 1967.

- Bolus, Malvina. People and Pelts: Selected Papers. Winnipeg: Peguis Publishers, 1972.

- Judd, Ballad Chiliad. and Arthur J. Ray, eds. Quondam Trails and New Directions: Papers of the 3rd Due north American Fur Trade Conference. Toronto: University of Toronto Printing, 1980.

- Buckley, Thomas C., ed. (1984). Rendezvous: Selected Papers of the Quaternary North American Fur Trade Conference, 1981. St. Paul, Minnesota.

- White, Bruce M. "Give Us a Little Milk: The Social and Cultural Meanings of Gift Giving in the Lake Superior Fur Trade". In Buckley (1984), pp. 185–197.

- Trigger, Bruce Grand., Morantz, Toby Elaine, and Louise Dechêne. Le Castor Fait Tout: Selected Papers of the 5th N American Fur Merchandise Conference, 1985. Montreal: The Society, 1987.

- Brown, Jennifer S. H., Eccles, Westward. J., and Donald P. Heldman. The Fur Trade Revisited: Selected Papers of the Sixth North American Fur Trade Conference, Mackinac Island, Michigan, 1991. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 1994.

- Fiske, Jo-Anne, Sleeper-Smith, Susan, and William Wicken, eds. New Faces of the Fur Trade: Selected Papers of the Seventh North American Fur Trade Conference, Halifax, Nova Scotia, 1995. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 1998.

- Johnston, Louise, ed. Aboriginal People and the Fur Trade: Proceedings of the eighth North American Fur Trade Conference, Akwesasne. Cornwall, Ontario: Akwesasne Notes Pub., 2001.

External links

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fur trade. |

- The Canadian Museum of Civilisation – Corking Fur Trade Canoes

- H. Bullock-Webster fonds – An album of color sketches, from the UBC Library Digital Collections, documenting social life and community in Canadian fur trade posts in the 19th Century

- A Brief History of the Fur Trade

- Map of trading posts, forts, trails and Indian tribes

- History of the Fur Trade in Russia Archived 2007-12-28 at the Wayback Car

- History of the Fur Merchandise in Wisconsin Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Museum of the Fur Trade, Chadron, Nebraska USA

- The Economical History of the Fur Merchandise: 1670 to 1870 (EH.Net Encyclopedia of Economic History)

- Fur merchandise in the Serpent River Valley, Idaho

- The Fur Trade Revisited – Manitoba Historical Guild

- The Papers of Hector Pitchforth on Fur Trade in the Chill at Dartmouth College Library

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fur_trade

Posted by: wilsongrem1973.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Which Of The Following Animals Has Fur That Changes Color With The Season?"

Post a Comment